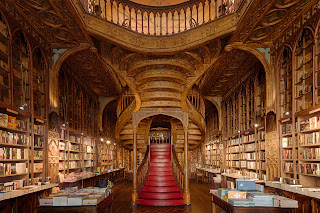

Sometime in the intermission between lock-downs, we escaped to Porto. The Pert Young Piece insisted we join the throng to gain admission to Livraria Lello. One pays to get in, and reclaims the expense against a purchase. Seems sound enough business practice, and I came away with a small anthology of Camões (whom I have frequently mentioned as part of the epic tradition, but never really read at any length). Despite the hordes desperate to view that Harry Potter stair-case, the bookseller took pity on my age, allowed me to sit and muse, and engaged me in conversation — at one point thrusting a Dickens first-edition into my hands.

I've never bothered to order my preference for Dickens' writings. On first thoughts, I prefer the later ones to anything before Copperfield (1850) — though even that ending is a trifle oily and unctuous for modern tastes. Probably bottom of the league, and teetering on relegation would be Chuzzlewit (1844), where I sense the creative juice was running a trifle thin.

On the other hand, there are the 'hard' novels — not just Our Mutual Friend (1865), because of its complexity, depth and length — but Bleak House (1853) and Hard Times (1854). Those latter two are my top spots.

12. Charles Dickens: Bleak House

I've been obsessing over openers above. The starter here, In Chancery, has to be exemplary. At his luxuriant best, Dickens develops a massive metaphor: a true 'London peculiar' and the fog of the judiciary:

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another's umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little 'prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds.

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time—as the gas seems to know, for it has a haggard and unwilling look.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln's Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

One of the few joys of A-level teaching is a 'bright' class cracking open their clean, new paperbacks. Quick clearing of throat, and I, the centre of attention, can indulge in those rolling paragraphs. Never deny the latent thesp in any teacher. With luck, one of the brightest of the bright may quibble over Megalosaurus:

Oh yes, indeed, my fine friend. And they were an English discovery. The Rev. Dr. William Buckland, Oxford geologist and (get this!) Dean of Westminster, found the first one in a slate quarry: it still has its place in Oxford University's museum of Natural History. 'Not many people know that!' (to be delivered in the rôle of Michael Caine). Other, different species started to come out of the strata, so Richard Owen (who thought Darwin's theory too simplistic) had to invent the omnibus term, 'dinosaur', in 1842.Did they really know of dinosaurs in the 1860s?

I saw before me, lying on the step, the mother of the dead child. She lay there with one arm creeping round a bar of the iron gate and seeming to embrace it. She lay there, who had so lately spoken to my mother. She lay there, a distressed, unsheltered, senseless creature. She who had brought my mother's letter, who could give me the only clue to where my mother was; she, who was to guide us to rescue and save her whom we had sought so far, who had come to this condition by some means connected with my mother that I could not follow, and might be passing beyond our reach and help at that moment; she lay there, and they stopped me! I saw but did not comprehend the solemn and compassionate look in Mr. Woodcourt's face. I saw but did not comprehend his touching the other [Bucket] on the breast to keep him back. I saw him stand uncovered in the bitter air, with a reverence for something. But my understanding for all this was gone.I even heard it said between them, "Shall she go?"

"She had better go. Her hands should be the first to touch her. They have a higher right than ours."

I passed on to the gate and stooped down. I lifted the heavy head, put the long dank hair aside, and turned the face. And it was my mother, cold and dead.

One can read into the story whatever one wishes: the law's delays, the foibles of fortune, Victorian moralities ...

Bucket often gets the credit of being the first detective in English fiction. The 'detective branch' of the Metropolitan Police date from 1842: CID wouldn't come along until 1878. Three articles by Dickens, from 1850 before he was formulating Bleak House, show his growing interest in the work of the detectives. In one, On Duty with Inspector Field, Dickens accompanied Field and his bag-man, Rogers, into the grim slums and cellars of 'the rookery of St Giles' (which would be swept away to make New Oxford Street and Charing Cross Road):

How many people may there be in London, who, if we had brought them deviously and blindfold, to this street, fifty paces from the Station House, and within call of Saint Giles's church, would know it for a not remote part of the city in which their lives are passed? How many, who amidst this compound of sickening smells, these heaps of filth, these tumbling houses, with all their vile contents, animate, and inanimate, slimily overflowing into the black road, would believe that they breathe THIS air? How much Red Tape may there be, that could look round on the faces which now hem us in - for our appearance here has caused a rush from all points to a common centre - the lowering foreheads, the sallow cheeks, the brutal eyes, the matted hair, the infected, vermin-haunted heaps of rags - and say, 'I have thought of this. I have not dismissed the thing. I have neither blustered it away, nor frozen it away, nor tied it up and put it away, nor smoothly said pooh, pooh! to it when it has been shown to me?'

Inspector Field is, to-night, the guardian genius of the British Museum. He is bringing his shrewd eye to bear on every corner of its solitary galleries, before he reports 'all right.' Suspicious of the Elgin marbles, and not to be done by cat-faced Egyptian giants with their hands upon their knees, Inspector Field, sagacious, vigilant, lamp in hand, throwing monstrous shadows on the walls and ceilings, passes through the spacious rooms. If a mummy trembled in an atom of its dusty covering, Inspector Field would say, 'Come out of that, Tom Green. I know you!' If the smallest 'Gonoph' about town were crouching at the bottom of a classic bath, Inspector Field would nose him with a finer scent than the ogre's, when adventurous Jack lay trembling in his kitchen copper. But all is quiet, and Inspector Field goes warily on, making little outward show of attending to anything in particular, just recognising the Ichthyosaurus as a familiar acquaintance, and wondering, perhaps, how the detectives did it in the days before the Flood.

No comments:

Post a Comment