Counting to a hundred …

I’m at the end of my chain with wordpress. The latest iteration/user-unfriendly-update is totally unusable with a Safari browser for input. Hence I'm looking to revert to Blogger.

Still, I’m seeking a way to fill space and occupy time. I started this racket to keep the Alzheimer's at bay — and, so far — it seems to be working.

I’m going to emulate, and I hope improve the multitude of webpages which tell us, with one or another level of credibility, the hundred books we all should read. Correction there: there cannot be a canonical list of the books anyone should read. My choice is subjective, the result of six decades as an active reader (and before that it was Biggles and worse). Give anybody a ddecent library, and turn that individual loose, to choose and reject.

Most of those definitive efforts are wholly vacuous. A dead give-away is listing both Hamlet and the Complete Shakespeare. I’m not convinced I’ve done the second of those — it was only in the last year or so I attended a performance, and then read the text (which I found significantly different) of The Two Noble Kinsmen. I’d argue that one is as much John Fletcher as yer ackshul Uncle Bill Shagsper.

But let me get him out of the way to start.

1. Julius Caesar

I give this one priority because it was the first that really ‘got’ to me.

I’d been fed Midsummer Night’s Dream in a mixed-class at Fakenham Grammar School (now defunct, for good or ill). Perhaps it was all those fairies that were supposed to ‘sell’ this to a captive audience, but it didn’t ‘sell’. Only decades later, when a daughter was doing that play for A-level, did I go back and have another try. That’s when I came across the editorial suggestions that MND is a deep political satire. Which opens a proverbial can-of-worms — but one not presentable to early adolescents.

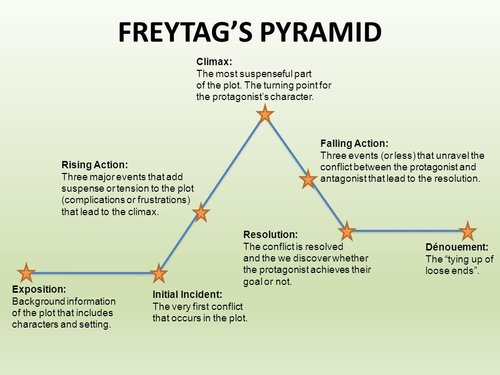

Then, for Irish Leaving Cert, we had to do a deep-ish study of Julius Caesar. Which meant learning large chunks of text. This time it all came together. If ever a play was made for all times and all societies, it’s this one. The characters are well-defined. The issues are authoritarianism, ambition, loyalty and opportunism. Assassination is a blood sport that constantly interrupts the flow of history. The structure of the play is impeccable: it fits Freytag’s pyramid precisely:

2. Antony and Cleopatra

I swear if you cut me, I’d bleed A&C. I had to teach it to two groups in two college years. That meant for sixteen hours a week I lived and breathed it. Without realising, I can still place much of the text, even to a particular page of the New (but not latest) Arden edition.

I’d maintain one of the funniest scenes in all Shakespeare is the one on Cleopatra’s tomb (the close rivals for that distinction are the two ‘assisted suicides’ in J.C.) . I could never read those without corpsing.

Judy Dench once reckoned the most difficult speech in all the corpus was Cleopatra’s ‘O!’ — and she does it repeatedly.

For sheer political cynicism there’s always Antony in J.C. and Octavius in A&C.

You may notice I don’t list any of:

- King Lear, which is based on the most eccentric pretext of a decaying monarch dividing his kingdom, has plenty of gore, includes the (unconscious) hilarity of the cliff-top scene, and comes with a truly gooey ending.

- Hamlet, if only because Omlette is far too complex for my mind (or those of the many critics) to fully comprehend. On top of which the treatment of Ophelia is even more gynophobic than Katerina in Shrew (for which, see below).

- Macbeth, because the play is so incomplete it barely holds together (we clearly have the shortened version, for royal entertainment mainly). I cannot truly engage with any of the characters — each is incomplete, and lacks real depth. The witchery is too crude for words. And I’ve had to teach it to the unwilling far too often.

3. Kiss Me Kate

Fair enough, unlike the above, not really a text.

It is, though, so wonderfully structured it is exemplary.

Kate/Katerina/Lilli is a remarkable part, and demands an equally-remarkable actor. In the original, in 1948-9 on Broadway and then in London, she was [Eileen] Patricia Morison — just one generation out of Belfast, and feisty with it. I saw the 2001 London transfer (after 9/11 did for Broadway) with Marin Mazzie and again the 2012 Chichester transfer, with Hannah Waddington.

To make the thing work, Kate/Lilli has to be in control all the way through — something the Kathryn Grayson/Howard Keel MGM movie doesn’t consistently achieve.

T here was a magnificent moment, one worth borrowing, in the 2013 Toby Frow Globe production of Shrew which made the whole farrago make perfect sense. In the first meeting of Katerina and Petruchio they exchange a mutually-knowing look (Beat … Beat …), as if each is recognising a worthy opponent.

here was a magnificent moment, one worth borrowing, in the 2013 Toby Frow Globe production of Shrew which made the whole farrago make perfect sense. In the first meeting of Katerina and Petruchio they exchange a mutually-knowing look (Beat … Beat …), as if each is recognising a worthy opponent.

And, with Kiss Me Kate, there are always the superb lyrics of Cole Porter.

Now, on with the motley, and some fiction …

Just bloody impossible

The latest upgrade to wordpress makes it totally unusable under Safari.

I don’t see myself continuing this blog under those constraints.

Back to blogger.com?

Been there. Got the sweat stains

That’s today’s New York Times.

The story starts with my ‘early retirement’, which meant a substantial lump-sum pay-out. Daughter #1 had other fish to fry, #2 had already done her American summer (it seemed to feature cleaning and refilling ketchup bottles in Estes Park, CO) — which qualified her to determine much of the route. #3 was old enough to be bored, young enough to be entertained by word games.

So, to spend the loot we did our own American trip: two weeks East Coast, fly to Denver, three weeks circuit of the Western States. This in an insane velour-lined ‘double-upgrade’ with a Utah plate.

Thus we arrived at Death Valley and Highway 190.

At Zabriskie Point, we paused, out of misplaced respect for Michelangelo Antonioni and Sam Shepherd. The two daughters refused to join us scrambling up the bank to observe the celebrated view. They were complaining because we were, of course, adhering to roadside instructions to switch off air-conditioning to avoid over-heating. I was watching the oil-temperature closely. One look around the bleak outlook suggested their reticence was well advised.

At Zabriskie Point, we paused, out of misplaced respect for Michelangelo Antonioni and Sam Shepherd. The two daughters refused to join us scrambling up the bank to observe the celebrated view. They were complaining because we were, of course, adhering to roadside instructions to switch off air-conditioning to avoid over-heating. I was watching the oil-temperature closely. One look around the bleak outlook suggested their reticence was well advised.

Onwards, then, and Furnace Creek. Somewhere along the road we passed a jogger, doing it the hard way despite the heat. Inevitably, his small back-pack sported a Union Jack.

Furnace Creek is the Visitor Centre, and chilled drinks. That got the young ideas out of the car.

Then an encounter with the National Park Warden. He admitted to spending his winter in a ski-ing resort.

Somewhere there must be photographs of us by the thermometer‚ which my memory says was registering something above 120 degrees F.

Phew!

Not so, we were told: ‘yesterday’ it hit 127.

After which, on to the balmy air of the Sequoia forest.

In passing, the ‘entertainment’ for #3 daughter on this trek involved Q+A on a listing of all the American Presidents: by that time we had just reached Bill Clinton.

I blame her addiction to US politics, her subsequent M.A. thesis, and much more on that.

Location, Location …

That previous posting came down to class: the 11+ and grammar schools gave the aspiring lower-middle class a route into white-collar employment. And consigned the 80% who didn’t make it to hewing wood, drawing water. In many local education authorities there were fewer ‘grammar school’ places for little girlies. And those sweet, dainty mademoiselles, who suffered from earlier ‘awareness’, had a discriminating subtraction to make sure they didn’t squeeze out the lads from the places that were available.

This posting continues along similar lines.

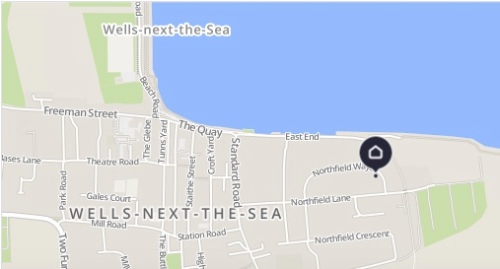

Two houses, both alike in dignity, in fair Wells, Norfolk, where we lay our scene … My links to Wells are shown in other postings on this blog. I wouldn’t want to go back (but I have been, for as brief a time as possible); but there is a persistent nostalgia. Above all, I never quite get over cottages, which in my time sold for the bottom end of three figures, now going for well into six numbers. Hence a gobsmacked addiction to local property porn.

My links to Wells are shown in other postings on this blog. I wouldn’t want to go back (but I have been, for as brief a time as possible); but there is a persistent nostalgia. Above all, I never quite get over cottages, which in my time sold for the bottom end of three figures, now going for well into six numbers. Hence a gobsmacked addiction to local property porn.

Now those two houses …

The terraced job on the left is:

I’d give small odds this charming Grade II Listed period brick and flint cottage is more brick to the rear, for just that reason. Were ‘Burnham Cottage’ mine, in mid-winter I’d keep a sharp eye on those ‘spring’ tides and flood warnings.

I’d give small odds this charming Grade II Listed period brick and flint cottage is more brick to the rear, for just that reason. Were ‘Burnham Cottage’ mine, in mid-winter I’d keep a sharp eye on those ‘spring’ tides and flood warnings.

ç is a semi detached ex-local authority house situated in a popular residential area within walking distance of the town centre at Wells-next-the-Sea with first floor views towards the sea and close to walks on the North Norfolk Coastal Path and East Quay.

Forgotten performers, the laughter of ghosts.

The Great Fowler, Christopher that is. The creator of the magnificent and — err— well-matched duo, Bryant and May.

Suzi Feay, in the current Guardian Review, warns me that:

This month London Bridge Is Falling Down, Fowler’s 20th Bryant & May crime novel, will be published, bringing to a close a much-loved series that started in 2003 with Full Dark House. The books feature the unconventional detective duo Arthur Bryant and John May of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit, who solve arcane murders whose occult significance baffles more traditional detectives. Crime fiction aficionados can amuse themselves by spotting references to classics of the golden age, whose plots and twists Fowler ingeniously projects on to the era of computers and mobile phones. Everyone else can enjoy the endlessly bantering and discursive dialogue between the pair as they break all procedural rules, and the uniquely droll narrative voice with its sharp-eyed slant on modern life.

Crime fiction is a very crowded genre. Anyone entering the trade has to stretch the envelope. Fowler described that:

When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle conceived Sherlock Holmes, why didn’t he give the famous consulting detective a few more quirks: a wooden leg, say, and an Oedipus complex? Well, Holmes didn’t need many physical tics or personality disorders; the very concept of a consulting detective was still fresh and original in 1887.

Holmes certainly comes with quirks. Each of his successors adds a few more. Fowler, though, tops the list. It is hard to come across any characters so outré as:

John and Arthur, inseparable, locked together by proximity to death, improbable friends for life.

John and Arthur, inseparable, locked together by proximity to death, improbable friends for life.

Nor an author who makes as if one of them is killed off on the first page of the first book in the sequence. Even Conan Doyle gave Sherlock twenty-six stories before despatching him (or not, as readers and revenue demanded) down the Reichenbach Falls:

Fowler adds another dimension: the trivia of London geography. In that first outing, he has Bryant and May located in the Palace Theatre, since 1891 that gloomy presence overlooking Cambridge Circus, and now since 2017 haunted by Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. May:

located the theatre archive in a room at the darkest turn in the corridor. Within the cramped suite were dozens of overstuffed boxes and damp cardboard files cataloguing productions and stars. Dim light was provided by the bare bulb overhead. He glanced across the titles on the lids of the boxes and pulled out some of the Palace’s monochrome publicity photographs. Buster Keaton performing with his father, the pair of them bowing to the audience in matching outfits. The jagged profile of Edith Sitwell, posturing her way through some kind of spoken-word concert. A playbill for W. C. Fields starring in a production of David Copperfield. Another presenting him in his first appearance at the Palace as an ‘eccentric juggler’. The four Marx Brothers, gurning for the camera. Fred Astaire starring in The Gay Divorcée, his last show before heading to Hollywood.

The dust on the lower boxes betrayed an even earlier age. The infamous Sarah Bernhardt season of 1892; Oscar Wilde’s Salome was due to have been performed at the theatre, but had fallen foul of the Lord Chamberlain’s ruling about the depiction of religious figures. The legendary Nijinsky, seen onstage just after his split with Diaghilev. According to the notes, he had left the Palace after discovering that he was to appear at the top of a common variety bill. Cicely Courtneidge in a creaky musical comedy, her dinner-jacketed suitors arranged about her like Selfridge’s mannequins. The first royal command performance, in 1912. Anna Pavlova dancing to Debussy. Max Miller in his ludicrous floral suit, pointing cheekily into the audience—’You know what I mean, don’t you, missus?’ Forgotten performers, the laughter of ghosts.

Counting those lately missing in action: Henning Mankell, Colin Dexter, Sue Grafton, Philip Kerr, John le Carré …

Alma matter

I’m just reading Ian Jack’s Diary for the current London Review of Books. Although he starts from a mention of  Selina Todd on post-War social mobility, or the lack (and Myth) of it, being Jack, after one paragraph, he gives a sketchy outline of educational thinking in the 1940-50s. That segue is achieved through something less sociological, more human, more approachable:

Selina Todd on post-War social mobility, or the lack (and Myth) of it, being Jack, after one paragraph, he gives a sketchy outline of educational thinking in the 1940-50s. That segue is achieved through something less sociological, more human, more approachable:

On a Monday in late August 1956, somewhere around two hundred of us waited in the assembly hall of Dunfermline High School, wondering what would come next. We had stood to sing the day’s hymn and sat bent to mutter the Lord’s Prayer — the Scottish version, debts and debtors rather than the sibilant trespasses and trespass — and then watched as older children, familiar with the school’s routine, filed out to start their lessons. Now we, the new intake, were told which class we would be in. There would be four classes for girls and four for boys, their gradations taking up the first eight letters of the alphabet, beginning with class 1A for girls and 1B for boys. As names were called, children stood up from the benches and gathered at the front, until an entire class had been assembled. A, B, C, D, E and F were called, and I was still there, waiting with around thirty other boys until the girls of class 1G had been led away, leaving us to be identified as 1H. There was no lower rank and no avoiding the fact that we were considered the least bright children in the school, who only just deserved to be there. I remember the shame.

At Fakenham Grammar School, I found myself first in the pits of the C-stream: initial sheeping/goating (and something ruminant in-between) was done on the basis of surname. After a term I was elevated to the middle stream; and only at the end of Year One did I ascend the Olympian heights of 2A. For that accelerando, I blame a total inability to cope with French particles. Still: I have the Year One Geography Prize (a case-bound copy of Monty James’s Suffolk and Norfolk) to show for it.

Erasmus Smith and all his works

I repeated the experience some years later, switching from the English GCE curriculum to Irish Leaving Certificate at the High School, then single-sex and at the top of Harcourt Street. Thus I found myself, week one, sitting at the left-hand end of one of those antique school desks Wackford Squeers would have recognised (position determined by fortnightly evaluations). While in normal circumstances the back-row is my chosen place in life, I gradually edged out (though to add to my existential problem with French, I now added Irish).

My break-through came with Eng Lit study of Winter’s Tale. The shepherdess Mopsa makes a love-demand:

Come: you promised me a tawdry-lace and a pair of sweet gloves.

The master threw out one of those questions that I would later, as a practitioner myself, recognise as vamp until ready while discreetly checking end-notes:

Anyone know what tawdry-lace means?

There’s always a smart-arse. Reader, that day, he was I.

Probably because my copy of the text (we had to buy our own) was a venerable edition, with a compendious literary apparatus, and I, bored by progress, was squirrelling there. Onwards and forwards: by week six (after the third assessment) into the front row. Latin grammar, History, and a certain fluency in English, trumped the MFL blindness. Not that the plank seats were any more easy on the bum.

We all contain versions of such anecdotes: Josie Holford (whom I ought to acknowledge more frequently) gave hers in a blog, And of Course We Called Her “Nutty”. Delicious stuff, well worth the trip.

The sociology of it all

In the midst of his academic memories, Ian Jack drops the killer:

Matching a personal to a general history rarely makes for a perfect fit. Todd says that more working-class children at grammar school were influenced by their mothers’ experience than by their fathers’, quoting the findings of the social scientists Jean Floud and Albert Halsey that such mothers were likely to have ‘received something more than an elementary schooling, and, before marriage, had followed an occupation “superior” to that of the father’.

For me, that’s the essence. My mother also went to Fakenham Grammar School: somewhere I’ve a photograph of the hockey 1st XI. As a girl, in those days, there was no higher education. So she became a nurse and midwife. Her sons, she made sure, were the first in the family’s memory to go to university.

The moral of the story?

Jack final paragraph comes close:

My own schooldays ended in 1962. In the academic year 1962-63 only 3.56 per cent of UK school leavers went to university and I wasn’t among them. In those days you needed Higher Latin to study English at Edinburgh. As Peter Cook’s miner says in Beyond the Fringe: ‘Yes, I could have been a judge but I never had the Latin. I never had the Latin for the judging. I didn’t have sufficient to get through the rigorous judging exams.’ The change began soon after. ‘By the end of the 1960s,’ Todd writes, ‘the value of giving everyone greater opportunity ... was more widely understood, particularly when it came to education. But this lesson was learned at the expense of thousands of children defined as “failures” at eleven years of age. They paid a high price for the illusion of meritocracy.’ And, she might have added, Britain’s still industrial economy paid that high price too.

Edinburgh University’s loss was journalism’s gain.

Is there another ‘me’ who missed out on a different, less academic, but fulfilling life? What happened in that parallel existence where, driven into the locked toilet by fear of another days of French particles, I resisted my Mother’s winkling threat:

‘Well, stay there. And go and get a job on the railway.”

Boris, not good enough

For almost a year, politics.ie has had a thread,

Boris Johnson’s administration is smelling of sleaze

I suspect it flourishes because:

- it represents an existential truth;

- it plays to negativism, one of the main drivers of many posters there;

- it kicks against the old enemy;

- it anatomises one of the more bizarre characters in modern politics.

So, I am reminded that all the best Tory scandals concern sex — let’s identify that as 💋for brevity; while all the best Labour ones involve money 💰. Oddly enough, in both cases, the persons involved stick to, and ultimately resign (or are resigned) by the rules 📕. And, until now, I never thought I would fall for emojis.

Johnson is different, especially in his contempt for 📕.

Yesterday’s Guardian had a column by Heather Stewart, its political editor, Boris Johnson yet again avoids paying the price for his cavalier attitude. Her focus is her starter, the Mustique jolly and therefore mainly 📕, but with added 💋 and incidental 💰for zest.

Stewart listed:

- Mustique: £15,000-worth of accommodation from the Carphone Warehouse co-founder David Ross. Ross, a vampire capitalist, says Private Eye and other sources, has a casual relationship with general 📕. Another dimension is the family fortune began with fish in Grimsby — so a touch of the #Brexits

.

- The Lulu Lytle/Carrie Antoinette ‘tart’s parlour’ at Downing Street, initially financed by £58,000 from Conservative peer, Lord Brownlow. Brownlow’s contributions to Tory funds were £714,690 in 2017, and his elevation to the Lords followed some months later. So mainly 💰and 📕.

- Jennifer Arcuri (always very much to the fore) gets short shrift on wikipedia. It suggests only a couple of bunces from public funds, and three overseas trips. Other sources go larger, and add in the hundred grand awarded to her firm. So a grand total of at least £126,000 for (admittedly) several years as Johnson’s grande horizontale. I’d award that another full house: 💋,💰and 📕

- Then there’s Peter Cruddas, City wide-boy, commuting ex-pat, who acquired a Lords nomination on the back of (his own claim) £1 million to the Tories — though only a third of that can be actually accounted. When the Lords soured on his nomination, he sealed it with a further £50,000 — and Johnson casually over-ruled the objections. 💰and 📕.

Stewart skims lightly over:

- Priti Patel’s bullying, which required a substantial pay-out to the bullied — 💰 and 📕.

- Jenrick playing footsie with former pornographer Richard Desmond, to do down Tower Hamlets rightful community charges. £12,000 of Desmond’s £50 million gain to the Tory party, money well spent. More 💰and 📕— even Jenrick acknowledged what he did was illegal.

- Re-treading Gavin Williamson as the most useless education minister in living memory. Williamson had been defenestrated from the defence ministry by Theresa May for security reasons. 📕.

Other highlights should include the catalogue of untruths Johnson has perpetrated from the Dispatch Box. No need to list them: Peter Stefanovic’s little movie does it 📕:

Not to mention Johnson’s decade-long tussles with the UK Statistics Authority. That goes back to his days as London Mayor, intensified over the spurious £350m a week for the NHS and continued over small matters such as Universal Credit 📕 Remember, folks, insisting on raw numbers makes one a ‘Labour stooge‘ (2011), or suffering from ‘amnesia‘, or guilty of ‘wilful distortion‘ (both 2017) 📕.

That’s not ‘smelling of sleaze’. It’s wallowing in it.

Personal confession: along the lines suggested by Noël Coward:

Elyot: Nasty insistent little tune.

Amanda: Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.

I have recurrent flashbacks to school poetry anthologies, and the tumpty-tumpty-tum stuff found there.

Yes, I know he was a bigot of the first holy water, and a near-fascist (his brother went the full trip), but Chesterton got so much correct:

Whorfianism

Around 1929, two linguists dropped a theory that we are limited in our appreciation by our personal semantics. The two were Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. This became the ‘Sapir-Whorf hypothesis’. Or Whorfianism.

So an Eskimo is alleged to have multiple words for ‘snow’. Oh, argue that amongst yourselves: I’ve had to sit through lectures on semantics and stuff; and have no intention of revisiting.

Then I went to the back-page, and Will Self’s column, in the current issue of The New European. Available at all good newsagents, and cheaper in Ireland than in the UK. Self claims to have spoken to an advanced shop-lifter, ripping off high-end shopping parks. And this is the core matter:

… in the old-style London criminal hierarchy … hoisters are pretty lowly creatures, even if they are stealing from high-end outlets. Up above them ascends a perverse pantheon of peculation, with kiters (passers of stolen cheques and other fraudulent financial instruments), fences, conmen and sundry other tea-leafs — all the way up too those ‘pavement artists’ also known as ‘the chaps’ or ‘the heavy mob’: those thieves inclined to enter banks or jewellers and at gunpoint relieve them of their cash and valuables. To be a celebrated ‘chap’ is to ascend to the paramount status and become a ‘face’.

Self says he learned that from his origins in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

His predecessor was Henry Mayhew. In London Labour and the London PoorMayhew itemised in painstaking, even tedious detail:

the Condition and Earnings of Those that Will Work, Those that Cannot Work, and Those that Will Not Work.

At the pits of Mayhew’s hierarchy would be the mudlarks, pre-teenagers picking through the slime and effluent of the Thames banks for anything with the slightest value.

At the pits of Mayhew’s hierarchy would be the mudlarks, pre-teenagers picking through the slime and effluent of the Thames banks for anything with the slightest value.

Down in the sewers were ‘toshers’, scavengers looking far valuables.

The ‘climbers’ were the (mainly, but not exclusively) boys climbing up and sweeping the inside of chimney flues.

At the start and end of working lives were the crossing sweepers, clearing paths through the mud and horse dung for ladies in crinoline skirts. The ‘dust’ they cleared would end up on “the Golden Dustman’, Noddy Boffin‘s dust-heaps behind King’s Cross. To understand that, we need to appreciate just how much horse-dropping fouled the streets of Victorian London (Lee Jackson estimates a thousand tons a day). Oh, and the ‘dust’ would be shipped up the Lee Valley to the market-gardens.

One more: ‘pure collectors’ — which must be the grossest euphemism of all. They hoiked up dog turds and delivered them to tanners, where the ‘material’ was used for dying and treating leather.

Above there I referred to Our Mutual Friend, Dickens’ longest, most complex of novels. It opens with Gaffer Hexam and his daughter Lizzie, rowing:

between Southwark bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.

Their search is for bodies.

When Dear Old Dad came back from the Second Unpleasantness, he was with Thames Division at Wapping. One of the river police’s tasks was bringing corpses, largely of suicides, to shore. He once recollected how, curiously, all those ended up on the north bank, because the coroner would pay a better honorarium.

There are probably Whorfianisms for all that.

Another Irish first!

Luke McGee tweets:

The wikipedia link is about a project from 1869, which propelled passengers a grand total of a hundred yards. Mr Beach, its onlie true begetter was defeated by Mayor ‘Boss’ Tweed and a stock-market crash.

Let us celebrate Charles Vignoles (engineer) and William Dargan (the contractor) who took, and made work an 1839 patent trialled at Wormwood Scrubs. This was the Dalkey Atmospheric Railway, which operated for ten years from 1844. It gave Brunel the notion for his short-lived effort, the South Devon Railway.

Vignoles’s implementation worked, while Brunel’s didn’t. The difference was Devon rats, who took a liking to the oiled leather used for closing the vacuum tube, while Vignoles used a metal protection.

So we have a permanent reminder (and an instructive example of translation problems) where the Dalkey pump house once stood:

Sphere: Related Content

No comments:

Post a Comment